What Is Neurohumanism?

In the last two decades or so neuroscience has come into bloom. Breakthroughs in everything from MRI imaging to pharmaceuticals have brought the hard science of thinking and feeling so far forward into public view that any OfficeMax is well stocked with books that promise to lower your brain age in just minutes a day. While many of these claims are based on sketchy and incomplete research, there is no doubt that recent breakthroughs in brain science have given us tantalizing new insights into the biology and chemistry of knowing. These offer the promise of optimizing many intellectual endeavors, especially learning; but there is an irony here. The more we learn about the hard science of the brain the more complex, nuanced, and interdependent its functions are revealed to be. Seen in this light, some of the familiar ways of applying science to improving our lives—the development of medications, for example—seem crude at best, and dangerous at worst.

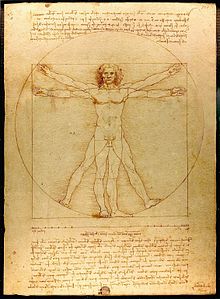

There is another way. In this age of constant innovation, it is easy to forget that there exists a field of human endeavor that has always been concerned with complexity, nuance, and the whole experience of what it means to be human. It's called humanism. First articulated during the Italian Renaissance, humanism by definition reaches back to even older currents in education, philosophy and the arts.

Philosophy? The arts? Aren't these the keepsakes of a quaint, bygone age, before the technocratic specialization of today's work life and the scientific, rational management of society?

No; not at all. As an educator, I am struck by how congruent contemporary trends in neuroscience and learning are with the core concepts of the humanities. Let's explore this common ground, ground on which we may walk as we navigate our daily intellectual lives.

Emphasis on creativity and innovation

Creativity has recently become a hot topic in educational reform—again—and it certainly is a core life skill in a culture that relies on creative destruction. Renaissance thinkers excelled at disruptive innovation, challenging religious dogma with philology, borrowing from the scholastic tradition even as they undermined it, and creating modern science out of natural philosophy. In a similar way, neuroscience is breaking down barriers between disciplines, leading to hybrids like psychoneuroimmunology and psychoneuroeconomics. Terms like these – or like "neurohumanism" – may seem awkward, but they point to the essential idea that without a grounding in the humanities, the technical arts may produce innovation, but never imagination; novelty, but never creativity.

Self-regulation and stress management

We have made great strides in our understanding of the deleterious effects of chronic stress to mind and body. Although neuroscience offers its own perspective and authority to this conversation, brain scientists did not invent the techniques they currently recommend; philosophers did. Meditation, moderation, respect for the body's care within the life of the mind, all are parts of the Western intellectual tradition. The now-familiar image of a Tibetan monk hooked it up to an fMRI machine shows us that neuroscience is in a position to bring together the ancient and modern, the humanistic and the scientific—bridging a gap that never really existed.

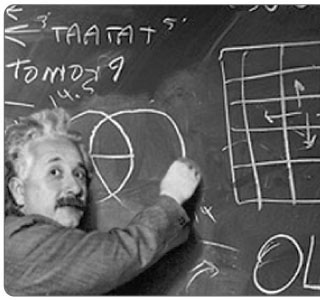

Empiricism

Some see in the efflorescence of neuroscience an overly mechanistic or reductive view of human nature, what Aldous Huxley called a "chemocracy." It would be more accurate to consider it a lesson in the value of the classic scientific method, applying observation to challenge accepted wisdom, but always with the awareness that our own conclusions will be similarly challenged and modified. Leonardo would be proud.

Optimism and positivism

Renaissance thinkers had a confidence in the human mind, one that goes well with scientific concepts like neuroplasticity. This ability of the brain to change and adapt over time may explain why practicing difficult skills—such as playing a musical instrument—improve executive attention (willpower), which is twice as predictive of academic success as IQ itself.

The irreplaceability of the human intellect

At first blush, this may seem to run counter to trends in neuroscience, some of which emphasize technological metaphors for the mind with book titles like iBrain and Mind Hacks. But actually neuroscience has demonstrated that the activities of the human brain and a computer differ not just in degree (speed, accuracy) but in essence. Cybernetics has a powerful presence and a bright future, but its past has shown us that artificial intelligence systems are nowhere near acting as our intellectual stunt doubles.

This train of thought is neither new nor unique. One can easily find similar connections between other frontiers of science and the humanities, just as modern science itself grows out of the ancient tradition of natural philosophy. What is new is the urgency with which we are called to make use of these points of contact. The pressure on us to think creatively, positively, and in an interdisciplinary fashion mounts every year, and not just on a societal level. Want to earn a living wage in this country? Learn to read critically, write persuasively, and speak fluently. Want to keep earning that wage in ten years? Learn how to learn, throughout the entire course of your life, because life itself is change. Petrarch paid homage to his classical role models by claiming that "dwarves standing on the shoulders of giants see farther than the giants themselves." Let's get started climbing onto the shoulders of dwarves, because we will need to see as far as possible.

— Andrew Lovett, 1/12/12

Contact

What Teachers Don't Know about Neuroscience

What Teachers Don't Know about NeuroscienceThis archived webinar is part of a series put on by The Learning Enhancement Corporation. This one is focused on "neuromyths" that teachers tend to carry with them in the classroom.

The Role of Social Media in the World's Revolutions: The Italian Renaissance

The Role of Social Media in the World's Revolutions: The Italian RenaissanceArt that would "change the face of nature and the hearts of men."

Are the humanities embattled?

Are the humanities embattled?There is something to be said for revisiting ideas that may not be new to humanity, but arise newly in each generation.